“The Nilgiri district may almost be said to be one of those happy countries which have no history.” — W. Francis, The Nilgiris (Gazetteer), Government of Madras.

When the history of the Nilgiris is told, it usually begins with the ‘discovery’ in the early 19th century, by John Sullivan, the collector of the Coimbatore district in the erstwhile Madras Presidency. For the longest time, it was believed that the Nilgiris had no history before the Europeans arrived, because the region remained, in colonial-speak, Terra Nullius — a land without a master or king.

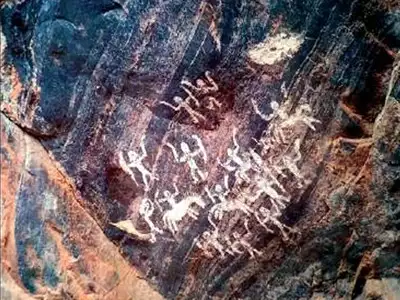

This completely dismissed the long and rich history of the indigenous people, the who had resided and thrived as herders and agriculturalists in the Nilgiris for centuries, living in harmony with the mountains, wildlife and with each other. They already had rich oral traditions, well designed community spaces and spiritual practices that kept them rooted to the environment.

It is true, though, that the arrival of the Europeans is a major turning point in the history of the Nilgiris but “official” histories tell us more about the narrow view that colonisers had of the indigenous cultures and peoples they colonised.

However, records clearly tell us that Sullivan and his team headed for the Nilgiri hills on January 2, 1819. They were so enchanted by the landscape that they, followed by a whole community of Europeans, settled in the Nilgiris for the salubrious climate and stayed on for tea and timber, right until India won her independence in 1947.

To his credit, and to the annoyance of his bosses, John Sullivan strongly advocated for the indigenous people of the Nilgiris to have considerable autonomy over their land. The administrations that followed, however, perceived the Nilgiris grasslands and sholas as wastelands and swamps, and very soon, set about acquiring land and reimagining the Nilgiris. Through architecture, agriculture, infrastructure and lifestyle, for better and worse, they transformed the mountains irrevocably, to invoke memories of their homeland. They developed a successful plantation economy and the charming hill stations of Ootacamund, Coonoor and Kotagiri. To enable their enterprise, Indians from across the subcontinent followed, escaping their own hardships like plagues, poverty, famine or oppression.

These significant interventions set the stage for more complex post-colonial changes that continue to redefine the Nilgiris today. The last two decades have seen a surge in migration to and from the Nilgiris. This exhibition puts the spotlight on this fragile landscape even as it showcases some rare photographs.

Read the full story that first appeared in Our Bangalore dated Feb 24-Mar 1, 2024 here:

A PDF is here: