To meet one of the only families of Sikligars or Swordsmiths of Rajasthan in Udaipur who continue to practice the traditional way of working with swords is an eye opener in more ways than one.

The din in the air is palpable and the sight in front of me is a smorgasbord of sensory experiences thanks to the riot of colour, art and craft. I am in the midst of the City Palace in Udaipur that is hosting its 4th World Living Heritage and in spite of all the brouhaha I am drawn towards an old man who is blissfully unaware as he is polishing a sword using what appears to be a wooden wheel that is held by a wooden stand that rotates. As I come closer, I see that the gentleman is Heeralal who is 90 years old and is incidentally the only traditional swordsmith who continues

The Swordsmiths

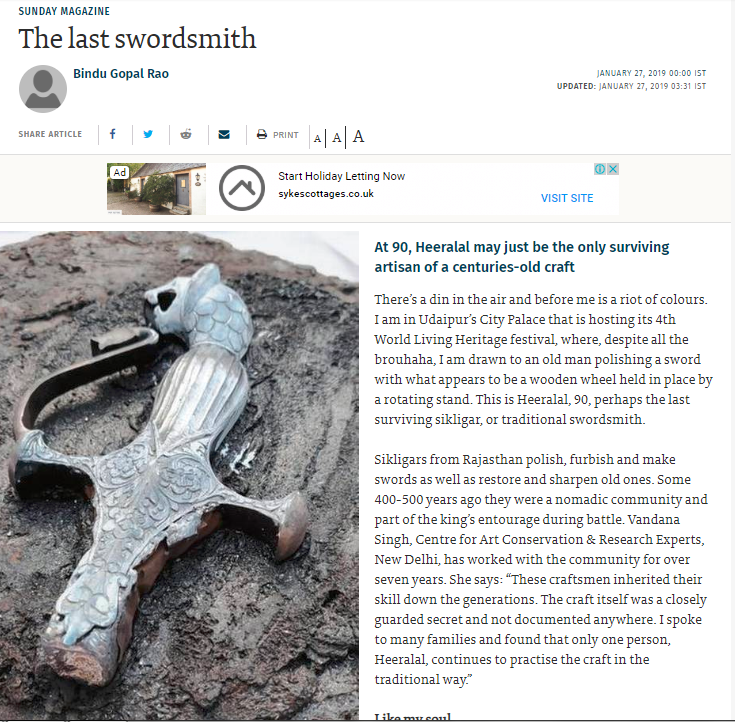

But before I start, let us find out a little bit about who the Sikligars are. This is a community of ironsmiths or sword makers of Rajasthan who are highly specialised in making fine swords. They polish, furnish and make swords as well as restore and sharpen swords. They were a nomadic community about 400-500 year ago and would be part of the king’s entourage as they would need to have their swords sharpened and ready for the battle. My interest is naturally piqued as I catch up with Vandana Singh, Centre for Art Conservation & Research Experts (CARE) New Delhi who has worked with the community over the last seven years. “These craftsmen have inherited their traditional skill which was passed from one generation to the next. The tradition itself was a closed guarded secret and was not really documented anywhere. I spoke to many families and found that only one person Heeralal continued to practice the craft in the traditional way.”

Tool Tales

Interestingly the traditional craft uses rudimentary tools for polishing the blades of the sword. This includes the emery stone, ashes, horse shoe, Ferni (blade sharpening machine) and deer horn for buffing as they do not leave any scratches on the surface of the blade. In fact the swordsmiths also use a traditional material for fixing handles on the sword blades that is referred to as Chapadi which is a mixture of river sand and lac melted together. The lac is found on twigs of some trees. Once the swords are ready they go into a traditional oven called batti and are quenched using sesame oil. The traditional way of tempering is that it is usually done during a moonless night when the colour would be clear and hence the swordsmith would know when to stop heating the sword. Ghanshyam, Heeralal’s son says, “my grandfather used to work with royals polishing and maintaining their swords. In fact he used to tell me that the sword must be polished using traditional tools rather than machines so that the temper is maintained. It also helped that in the post the quality of iron was superlative which is not the case is today. In fact the more metals in the composition of the iron the more it would cost back then. Just like a sculptor sculpts his work, we work with our hands to make sure it has a desired shape.”

The Swords of the Spirit

For the swordsmiths like Heeralal, the swords mean everything to them and rightly so. “The sword is like my soul I cannot leave what I do. I do not worry whether I can make money or not. The sword is a part of me and I value it far too much to let it go.” In fact the swords are prayed to and celebrated during the annual nine day Navratri festivities when they are worshipped by placing them in front of the idol of the Goddess and are believed to gain magical powers. “They consider these objects entirely differently as spiritually charged ritual objects rather than just a sword. They believe in the importance of the power within the object rather than its external form,” explains Singh who has experienced these rituals first hand. After nine days, the sword is removed and taken out on a procession in the village and there is a big celebration. As part of the festivities, the villagers dance with the sword and some also hit themselves with the sword as an act of asking to be pardoned for their past misgivings. The swords are revered and are seen as a way of experiencing the healing energy of Goddess and a way to connect with the higher being. In fact they also keep the sword below the head of pregnant women when they sleep as they believe this will ward off evil spirits.

Tech meets Tradition

Traditional conservation techniques are part of the Arm and Armours project at the City Palace, Udaipur and Shriji Arvind Singh Mewar of Udaipur, the 76th custodian of the House of Mewar is overseeing the effort. Singh and her team are working on cleaning, conserving and restoring as well as documenting the weapons at the armoury here. Singh and her team are merging traditional smithing with advance nano materials to restore and repair swords. Use of advance nano crystalline materials like alumina powder and silicon carbide powder and synthesis of new composite material from traditional adhesives has helped in this process. “Carbon Fibres and Carbon Nanotubes have been used as the reinforced materials and pure lac is used as a matrix material. These are nontoxic and biodegradable in nature and open up new potentialities in order to use them in other fields of art conservation and other scientific applications too,” avers Singh. However with most things traditional, the challenge is that the lack of demand for swords has meant that Sikligars have changed their business to making scissors. However all is not lost as Singh and her team has started documenting this dying art by interviewing the remaining traditional swordsmiths and also organise live demonstrations to rekindle the art. Slowly but surely the Sikligars are being recognized in many forums that has restored the pride in the craft and seems like there is hope for the Sikligars, after all.

This story first appeared in The Hindu Sunday magazine dated 27th Jan 2019 here:

Very quickly this web page will be famous amid all blogging visitors,

due to it’s good articles

Thank you for your kind words

Excellent article…Will you be able to give their contact details…

I have emailed you he number Rajesh

Please send me heralal’s number

You information is very valuable .I need it.thanks. please give me their contact. Heera lal ji

Priceless.please give Heera lal ji

Contact information. Thanks.

Hi Bindu,

Can you please mail me Heeralaal’s contact details ?

Please check mail.